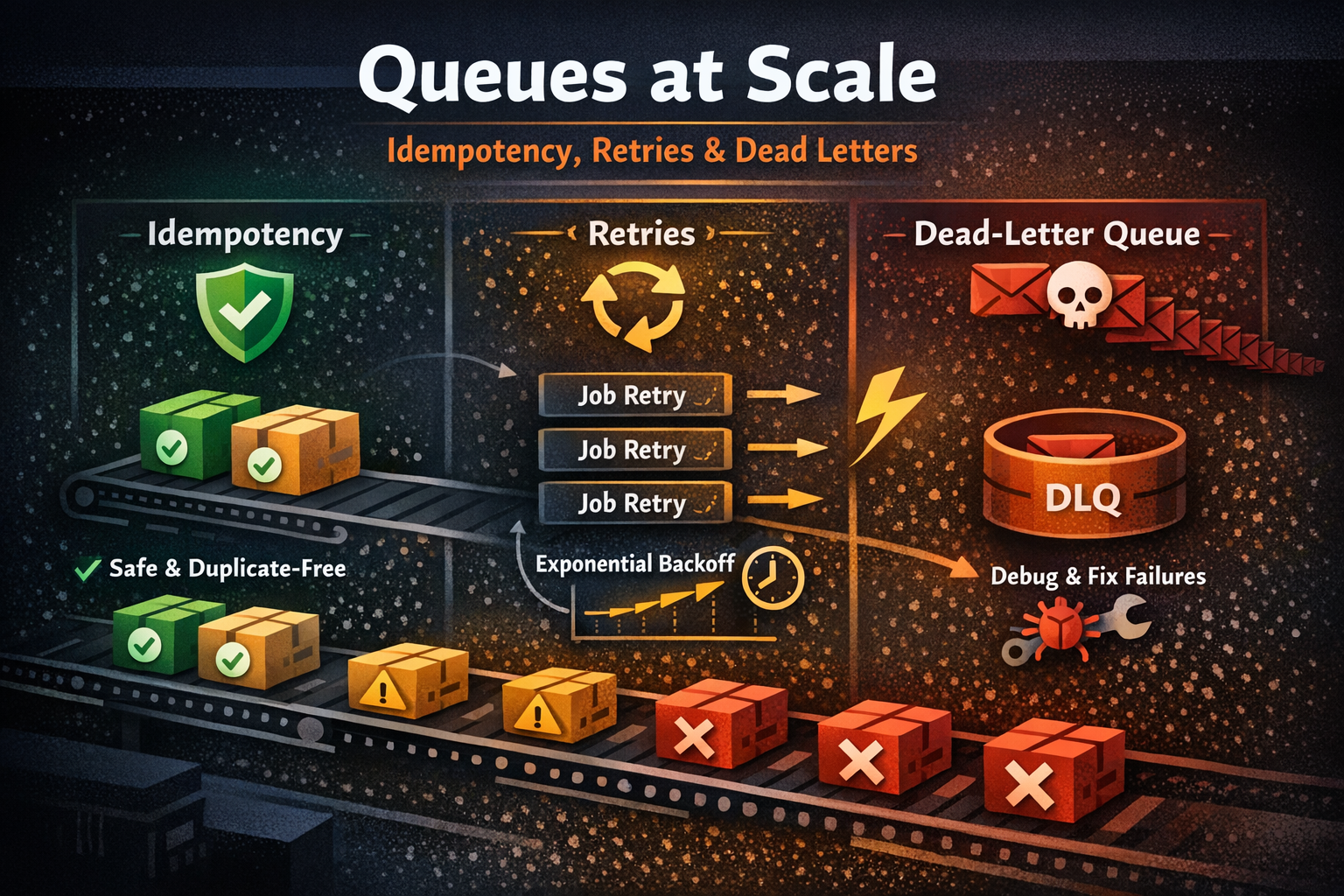

Queues at scale: idempotency, retries, dead letters — a practical guide

A hands-on guide to building reliable queue systems in production: idempotency, smart retries, backoff strategies, and dead-letter queues—without duplicate jobs, retry storms, or hidden failures.

Queues look simple until your system is under real load.

At small scale, you can usually get away with:

- “Just retry it”

- “It probably won’t run twice”

- “We’ll check logs if something breaks”

At scale, that mindset turns into:

- Duplicate emails sent to customers

- Orders processed twice

- Infinite retry loops burning CPU and money

- Poison messages blocking entire queues

This post is a practical guide to three concepts that make or break queue-based systems in production:

- Idempotency (doing things safely more than once)

- Retries (when and how to retry without making things worse)

- Dead-letter queues (what to do when a message is truly broken)

Examples are generic, but this applies directly to Laravel queues, SQS, RabbitMQ, Kafka consumers, etc.

1. First: assume your job WILL run more than once

If you take only one thing from this article, take this:

At scale, every job must be safe to run multiple times.

Why?

- Workers crash mid-job

- Timeouts happen

- Network calls fail after the remote side already processed the request

- The queue system may redeliver the same message

- You may manually retry jobs

So you must design jobs to be idempotent.

2. Idempotency: making “run twice” safe

Idempotent means:

Running the same job 1 time or 10 times produces the same final result.

❌ Bad example (not idempotent)

public function handle()

{

Order::find($this->orderId)->markAsPaid();

Invoice::createForOrder($this->orderId);

Mail::to($user)->send(new OrderPaidMail());

}

If this runs twice:

- You may mark the order paid twice

- You may create two invoices

- You may send two emails 😬

✅ Better: guard with state

public function handle()

{

$order = Order::find($this->orderId);

if ($order->status === 'paid') {

return; // already processed, safe exit

}

DB::transaction(function () use ($order) {

$order->markAsPaid();

Invoice::firstOrCreate([

'order_id' => $order->id,

]);

Mail::to($order->user)->send(new OrderPaidMail());

});

}

Key ideas:

- Check current state first

- Use unique constraints / firstOrCreate

- Wrap critical changes in transactions

- Design side effects to be deduplicated

Even better: idempotency keys

For external APIs or critical operations:

- Store a unique idempotency key (e.g.

event_id,message_id) - Before processing, check if it was already handled

- If yes → exit safely

This is mandatory when dealing with:

- Payments

- Webhooks

- Inventory changes

- Email/SMS sending

3. Retries: when “just retry” becomes dangerous

Retries are good. Blind retries are not.

The 3 types of failures

Transient (good for retries)

- Network timeout

- Temporary DB overload

- 3rd-party API hiccup

Persistent (retries will never fix it)

- Invalid payload

- Missing database record

- Business rule violation

Poison (breaks your worker every time)

- Bug in code

- Unexpected data shape

- Serialization issues

If you retry everything blindly:

- You waste resources

- You block queues

- You hide real bugs

- You create retry storms under load

4. Smart retry strategy

1) Limit retries

Always cap retries:

- Laravel:

$tries = 5 - SQS / RabbitMQ: max receive count

- Kafka: max attempts or backoff strategy

After N attempts → stop and move to DLQ.

2) Use backoff (very important)

Instead of retrying immediately:

- 10s → 30s → 2m → 10m → 1h

This:

- Reduces pressure on dependencies

- Avoids retry storms

- Gives time for transient issues to recover

In Laravel:

public function backoff()

{

return [10, 30, 120, 600];

}

3) Classify errors

Inside your job:

try {

$this->callExternalApi();

} catch (TemporaryNetworkException $e) {

throw $e; // retry

} catch (InvalidPayloadException $e) {

$this->fail($e); // do NOT retry

}

Rule of thumb:

- Transient error → retry

- Logic/data error → fail fast → DLQ

5. Dead-letter queues: your safety net

A Dead-Letter Queue (DLQ) is where messages go when:

- They exceeded max retries

- They are explicitly marked as failed

- They keep crashing workers

This is not a graveyard. It’s a debugging tool.

What should you do with DLQ messages?

- Log them with full context

- Alert when DLQ rate increases

Build a small admin tool to:

- Inspect payload

- See error reason

- Replay the job after fixing the issue

Common DLQ causes in real systems

- Code deployed that can’t handle older messages

- Data shape changed

- Missing foreign keys

- Assumptions that were never true in production

If you don’t have DLQs:

You’re either losing data silently or blocking your queues without knowing.

6. The “production-grade” checklist

If your queue system does all of this, you’re in good shape:

- ✅ Jobs are idempotent

- ✅ Side effects are deduplicated

- ✅ Retries are capped

- ✅ Retries use backoff

- ✅ Transient vs permanent errors are distinguished

- ✅ Dead-letter queue is enabled

- ✅ DLQ is monitored

- ✅ You can replay failed jobs safely

7. The uncomfortable truth

Most queue bugs only appear under load, partial failures, or bad data.

That’s why:

- Local tests pass

- Staging looks fine

- Production explodes at 10× traffic

Designing for retries, duplicates, and failures is not “over-engineering”.

It’s the difference between a system that degrades gracefully and one that wakes you up at 3am.

8. Final thought

Queues don’t make systems reliable.

Defensive design does.

If you want queues that scale:

- Assume duplication

- Expect failure

- Design for recovery, not perfection